by Richard Weil, M.Ed., CDE

Founder and Director

Transformation Weight Control

www.transformationweightcontrol.com

See images at the end of the post which illustrate and clarify some of the content.

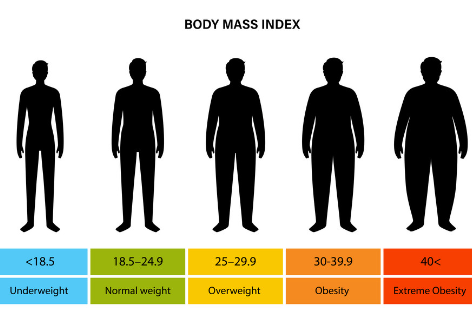

BMI

A bit of background.

The original BMI was created in the 1830’s by Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian astronomer, mathematician, statistician, and sociologist. He called it the Quetelet index and developed it to calculate an ideal weight based on height based on the premise that weight is relative to height. It was to be used as an index to categorize individuals. Quetelet did not develop this to estimate body fat or health risk, as it is frequently used today. His work was performed before the days of large epidemiological studies, where very large populations of people are studied for the association between height and weight, and the risk of diseases such as cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, stroke, and diabetes, amongst other chronic diseases.

Then along came Ancel Keys and his colleagues who published a paper in 1972 (citation #1) in which they coined the term “Body Mass Index” or BMI, based on the work of Quetelet, to determine risk of chronic diseases based on the ratio of weight to height. Like the Quetelet index, it is used for its simplicity and applicability to entire populations in large epidemiological studies as a way to estimate health risk based on weight and height, and as a rough estimate of body fat. It is calculated by taking a person’s weight in kilograms and dividing it by the square of their height in meters. If you prefer the English version, you divide the weight in pounds by height in inches squared and then multiply by a conversion factor of 703. Here’s an example, say you weigh 250 pounds and you are 68 inches tall. The equation would look like this: 250/68 squared (250 divided by 68 squared which is 68×68= 4624), and then multiply by 703, which would be a BMI of 38, which is exactly right. And if math is not your forte, you can have your BMI automatically calculated here: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmicalc.htm

Unfortunately, although BMI is simple and convenient to calculate with just height and weight, there are a number of limitations for using it as a tool for measuring body fat and health risk. Those limitations are the following:

- BMI does not give you a value for the overall amount of body and muscle in the body.

- BMI does not identify the location or distribution of body fat. For example, lower body fat is not as hazardous to your health as abdominal, or central fat, and the well-known and very dangerous body fat knowns as visceral fat. More about visceral fat in a moment. So, this is to say that if you had a high BMI but your body fat was located in the lower extremities, it is well-known that this fat is associated with lower health risk than someone with the same BMI but with body fat located in the belly.

- BMI does not differentiate between lean body mass (muscle and all other tissue except fat) and fat mass. For instance, a professional football running back could be 5’10” and weigh 225 pounds, and have lots of muscle and less than 6% body fat, but they would have a BMI of 32.3, which would put them in the category of having obesity, but obviously, with such low body fat, they do not have obesity. Doctors and scientists acknowledge the limitations of BMI for some to many individuals, but use it as a way to index and categorize people in large population studies.

- The BMI chart has not been updated to reflect the increase in the average height of adults over the years.

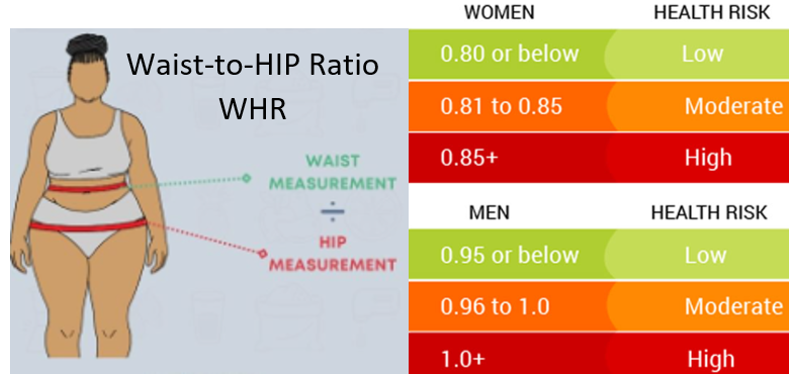

Waist-to-Hip Ratio

Another method of assessing health risk from anthropometric measurements is to use the Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR). WHR is measured by dividing the waist circumference by hip circumference (waist/hip). If someone has a waist of 40 inches and hips of 46 inches, then their WHR is .87 (40 divided by 46 — 40/46). The World Health Organization considers a woman with a WHR greater than 0.85 and a man with a WHR greater than 0.90 as having obesity. WHR has been shown in some studies to be superior to waist circumference or BMI as a predictor of cardiovascular disease and other chronic health conditions, while other studies show waist circumference to be a better predictor of chronic disease such as cardiovascular disease.

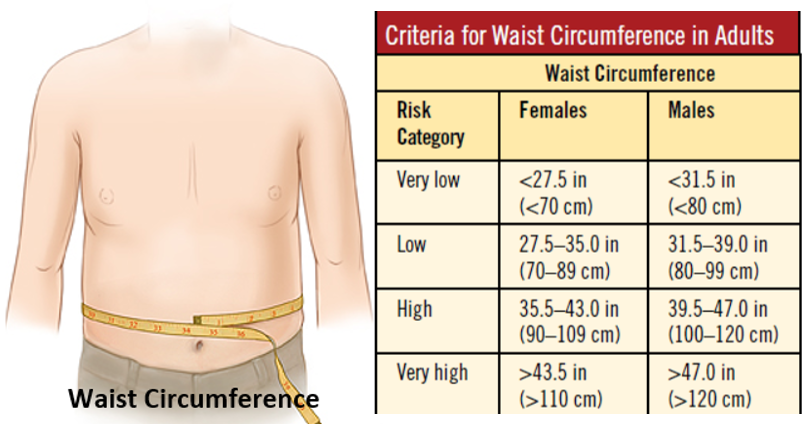

Waist Circumference

This is a bit of a misnomer. We refer to it as waist circumference, but in fact it’s the circumference around the widest part of the abdomen, typically around the belly button. Your waist is anatomically considered a little higher than this, around the narrowest part of the abdomen, usually above the navel and about 3 inches below the lowest rib. A waist circumference greater than 40 inches for men and 35 inches for women is considered high risk for chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, high blood pressure, and metabolic complications such as type 2 diabetes.

Visceral Fat

The reason WHR and Waist Circumference are good predictors of health is because they make an accurate estimate of visceral fat, the fat deep in the abdomen, that infiltrates and surrounds organs such as the pancreas and liver, which causes dysfunction in the organs affected, and can lead to cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and other chronic health conditions. Visceral fat is located below subcutaneous fat, the fat just below the skin that you can pinch (see the illustration below). WHR and Waist Circumference in the medical and scientific fields are known as “proxies” for visceral fat, which is to say they have high correlations between their value when calculated and the amount of visceral fat. Visceral fat can be measured more accurately using MRI or DEXA scan, but those methods are inconvenient, impractical, and expensive, plus, DEXA uses radiation – although just the equivalent of what you get with a standard x-ray, but still, it is x-ray.

Which to Use?

The research is somewhat mixed on which biomarker is the best way to assess health and visceral fat. In some studies, waist circumference does a better job, and in other studies, waist-to-hip does a better job. It’s clear that BMI is the least effective, although it does have some merit and should not be entirely excluded. In an important study, Gadekar and colleagues (citation #2), in 2020, published a study which showed that WHR did about a 23% better job than waist circumference to estimate visceral body fat, but other studies do not always show this, and it’s difficult to quantify exactly how much difference in health outcomes you can determine from using proxies for visceral fat such as WHR and waist circumference.

In our program, we use waist circumference or WHR to as a way to assess health risk and, to some degree, overall body fat (subcutaneous and visceral), although neither is as accurate as MRI or DEXA. As for BMI, we use it sparingly, usually just as a way to quickly categorize our population without having to take any measurements. For instance, we use it when we talk about the population-at-large; we can use it to say that the average BMI of our population is “X”, and this way we can get a quick picture of our population without having to use a tape measure to take any physical measurements. Weight and height to determine BMI is much easier to ascertain. But we do not use BMI as an accurate method to make conclusions about the health or body fat of our participants.

How to Take Waist Circumference and Waist-to-Hip Measurements

It may be helpful to have someone else take these measurements for you.

For waist circumference, stand up straight, exhale, and using a flexible measuring tape, wrap it around the widest section of your abdomen, usually around the belly button. Make sure the tape remains parallel to the floor, and pull gently, but firmly, until the skin indents just a little.

For WHR, stand up straight, exhale, and take the measurement around the smallest part of your waist, usually above the belly button and close to, but below, the lowest rib. Then wrap the tape around the widest part of the hips, usually the widest part of the buttocks. Then divide the hip measurement into the abdominal measurement. For example, as I mentioned above, if you have 40 inches for waist and 46 inches for hip, divide 40 by 46, and the WHR is .87 (40 divided by 46 — 40/46).

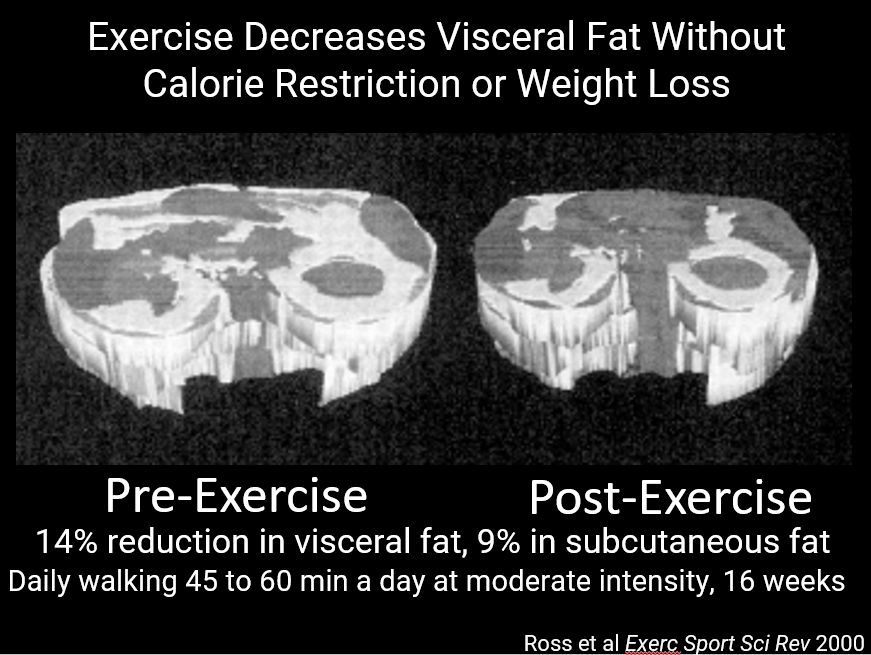

Good News About Visceral Fat

Visceral fat is very sensitive to exercise alone, weight loss alone, or both. The slide below shows a before and after MRI of visceral fat at the level of the belly button with the spine in front. What you are looking at is the result of a study of 45 to 60 minutes of walking per day at a moderate intensity for 16 weeks, without calorie restriction or weight loss. Visceral fat was reduced by 14%. This is just from only exercise (walking).

My Recommendation

If you’re curious and inclined, measure both waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Both are excellent predictors of good health and representative of the amount of visceral fat in your abdomen.

Citations

1) Keys et al. Indices of relative weight and obesity. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 1972.

2) Gadaker et al. Correlation of visceral body fat with waist–hip ratio, waist circumference and body mass index in healthy adults: A cross sectional study, in Med J Armed Forces in India, 2020.

IMAGES

Good News About Visceral Fat

Visceral fat is very sensitive to exercise alone, weight loss alone, or both. The slide below shows the MRI results from a study of the effect on visceral fat after 16 weeks of walking for 45-60 minutes once a day at a moderate intensity. There is no subcutaneous fat in these images. It has been removed from the image. What you see is the MRI image at the level of the belly button with the spine in front. White is the visceral fat, and the dark regions are organs and muscle. You can see that even though there was no calorie restriction nor weight loss, visceral fat decreased 14%. This is a clinically significant change in visceral fat which will lead to a healthier body.

© 2024 Richard Weil, All Rights Reserved