By Rich Weil, M.Ed., CDE

Transformation Weight Control

transformationweightcontrol.com

Distraction tasks are designed to direct your attention away from, take your mind off of, or decrease negative experiences such as obsessive thoughts, high arousal and anxiety during high-risk situations, overwhelming negative thoughts and emotions (sometimes associated with PTSD), intrusive and/or pessimistic thoughts, and other high-risk situations. Distraction techniques include a wide variety of strategies. Counting objects around you (e.g., how many red objects are in the room?), counting backwards from 100 by 2 or 3, reciting the alphabet backward, breathing in for a count of four seconds – then holding your breath for four seconds – then exhale for four seconds, body scans where you think about different muscles or regions of your body and contract and create tension in the regions, play with modeling clay (a common technique used in many studies), visual imagery of relaxing places, writing a letter to a good friend, drawing pictures or using a coloring book (popular in the past few years because pretty much anyone can do it and it looks nice), watch a funny movie or YouTube video, snap a rubber band on your wrist, tapping, and more.

My Tapping Experiment

I designed a tapping experiment to distract subjects from intense food cravings and the vividness of the image of the trigger food. I used participants from our weight control program as subjects since it was convenient and easier than recruiting subjects (appropriately called a “convenience sample”). There were 55 participants, with an average BMI of 43.7, (anything above 30 is considered having obesity, 43.7 is approximately 82 pounds into the category of having obesity). I collaborated with a psychologist in Australia, Dr. Andrew McClelland, who used the same protocol on lean individuals.

The experimental protocol was as follows:

- Subjects were asked to identify their favorite trigger food. In order, the favorite foods were: cheese, pasta, ice cream, pizza, chocolate, bread, chicken, steak, French fries, and rice.

- They were then read a script asking them for one minute to focus on the trigger food, the taste, the smell, how it feels in your mouth, and the experience of consuming it.

- Then they were asked to rate, on a scale of 0-100 (a visual analog scale), 100 being the highest, how intense the food craving was and then how vivid the image of the food was.

- Then they were asked to do one of four techniques for 30 seconds (some subjects were asked to do only 10 seconds) which I will explain in a moment.

- Then they were asked to repeat #3, rating on a scale of 0-100 how intense the food craving was and then how vivid the image of the food was.

Protocol expressed as a time line:

Identify favorite craving food –> Focus on the trigger food –> Rate the craving intensity and vividness of the image of the food on a scale from 0-100 –> Perform a tapping technique for 30 seconds –> Rate the craving and vividness again on a 0-100 scale and compare the value to the results before the tapping.

The idea was to compare the results of the visual analog scale from before the tapping task to after, and determine if the distraction tasks reduced the cravings and vividness of the food from.

Tapping Tasks Described

The tapping tasks and control were all conducted for 30 seconds. See videos at end of blog for demonstrations of the tapping techniques. They included:

- Tapping across the forehead from the side of the temple on one side of the head to the other, tapping once every second, tracking your finger with your eyes.

- Tapping around the entire ear in circles for 30 seconds,

- Sitting at a table with your feet out of sight and tapping with one foot in a pre-determined pattern. I chose this a technique so you could use it at a restaurant so no one would know. Tapping across your forehead or ear would be more conspicuous!

- Staring at a blank white wall. This technique was the control. The control in an experiment is a benchmark to compare to the effects of the other techniques. Ideally it is selected such that it does not cause any effect on whatever you are studying.

Every experiment has a hypothesis.

A hypothesis is a prediction of sorts as to how the experiment will come out, and determine through statistical analysis whether you have proven your prediction to be true or not. But a proper hypothesis is written as “how the world is”.

My primary hypothesis was the following:

Tapping across the forehead reduces food cravings and vividness of the image of the trigger food more than tapping on the ear or tapping the foot under a table.

My secondary hypothesis was the following:

Tapping around the ear reduces food cravings and vividness of the image of the trigger food more than tapping under the table with the foot.

Why I designed the experiment the way I did.

The rationale for the design of my experiment was based on the premise that vision is the strongest cue for a trigger food (more than taste, smell, odor, or talking about it), and so I used forehead tapping where the yes tracked the finger as a way to distract and affect vision, whereas the other two tapping techniques eliminated the use of vision. There’s a region in the brain known as the visuo-spatial sketchpad, and the theory is that you can only store so much information on the sketchpad (it’s why food cravings seem to occupy some or all of your thinking), that is, the visuo-spatial sketchpad can only store so much information. For example, think deeply about a rose, an automobile, and your favorite animal. Can you think deeply about all three at once? Almost certainly not; that’s because your sketchpad is capable of storing limited amounts of visual imagery, especially when thinking deeply about the object.

My hypotheses then were based on the theory that including vision in the tapping task by tracking the finger with the subjects’ eyes would wipe out the craving and vividness of the food in the visuo-spatial sketchpad more than the other tasks which eliminated vision.

My results, was I right?

The results of the experiment were just as I had hypothesized. Tapping across the forehead reduced the intensity of the food craving and vividness of the image of the food more than tapping around the ear or under the table with the foot. The ear was more effective than the foot under the table. So then, the order of effectiveness was:

#1 Tapping across the forehead,

#2 Tapping around the ear, and

#3 Tapping with the foot under the table. I think tapping around the ear came in second because it had an indirect effect on the sketchpad in the brain because the tapping was closer to the brain, whereas the foot tapping was as far from the brain as I could design.

Graphing the results.

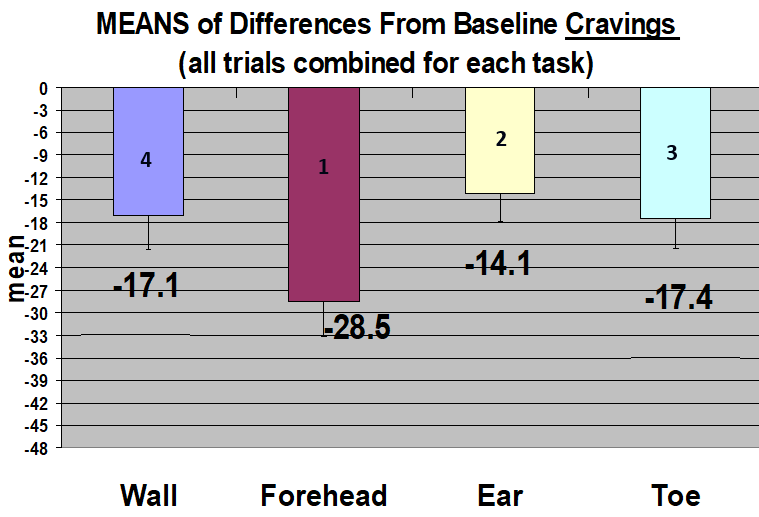

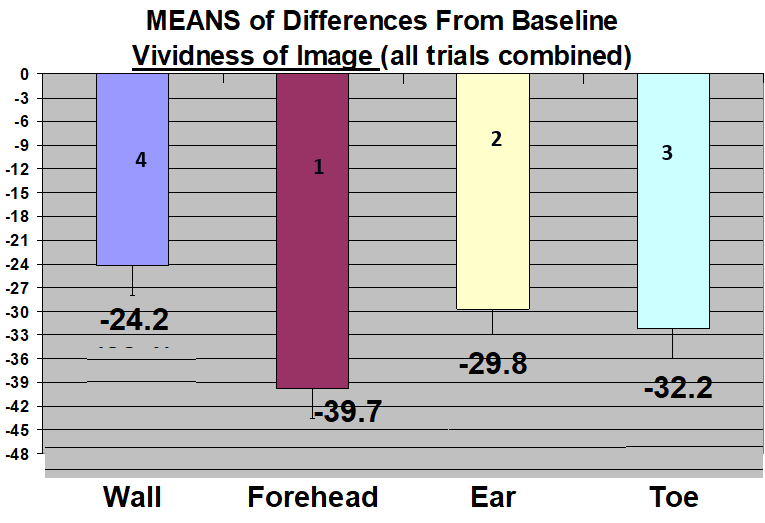

Below are graphs of the results. You can see that in each graph (cravings and vividness of the food image), the columns show that forehead tapping reduced cravings the most on the 0-100 scale (down an average of 28.5 points and down an average of 39.7 points in the vividness of image). The more negative the number the better the result.

Cravings Graph

Vividness of Image Graph

Two interesting observations.

An interesting side note is that when Dr. McClelland reviewed my data, he observed that the control (staring at the white wall) also had an effect and concluded that the data must be wrong. The wall was supposed to be the control, producing no result. I found out after speaking with the study participants, that staring at the white wall reminded them of a task we taught many years ago where you imagined a white window shade pulled done right in front of your face. Turns out, the white wall reminded the participants of the window shade and so it produced results! This didn’t help the analysis of our data.

Another interesting side note is that we conducted the study right before Halloween, and participants reported to me that the tapping helped them eat less candy!

Do I have to tap for 30 seconds?

The final note I want to add is that in a subset of the population of participants, we used 10 seconds for tapping, and the results were similar to tapping for 30 seconds, so it doesn’t seem to take much time to distract from cravings and images of the trigger foods using tapping techniques.

My final comment.

The experiment was a success and we were very pleased with the results. Perhaps you’ll experiment with some of these tapping techniques when your arousal or anxiety is high for any reason, or you have food cravings. I welcome your comments.

Tap away!

Below are videos of me demonstrating the tapping tasks.

Forehead Tapping

Ear Tapping

Toe Tapping

© 2024 Richard Weil All Rights Reserved