by Rich Weil, M.Ed., CDE

Founder and Director

Transformation Weight Control

“Any one of us could be an addict at any time. Addiction is not fundamentally a moral failing — it’s not a disease of weak-willed losers. When you look at the biology, the only model of addiction that makes sense is a disease-based model, and the only attitude towards addicts that makes sense is one of compassion.” David Linden

Nothing captures the essence of addiction more than these words by David Linden. It captures the depression, guilt, shame, and isolation of addiction. About 35 years ago I started thinking about food and eating as an addiction because after listening to my clients and patients who struggled with their weight, food cravings, overeating, lack of appetite regulation, and obsessing about food, it sounded just like it. The compulsions and obsessing over food they described, the intensity and vividness of the cravings, the inability to stop eating even though it caused psychic and physical pain. It all sounded just like addiction.

Then, in the late 1980’s, I read the book “Relapse Prevention” by Alan Marlatt and Judith Gordon. At the time, Dr. Marlatt was the world’s leading authority on alcohol addiction. He literally wrote the book on it! As I read it, it started to confirm what I believed to be true, that there is such a thing as food addiction, because everywhere he mentioned alcohol, I could easily have substituted the word “food”. I made notes throughout the book. I even remember where I started reading it, on a park bench in Washington Square Park in New York City, near where I lived. I think I’ve used the phrase, “rocked my world” once in my life, and reading his book did indeed rock my world. From then on, I started teaching my clients about food addiction, and it resonated strongly. However, when I would mention it to clinicians and researchers in the obesity/weight control field, it was difficult to sell the idea and, for decades, even to the present day, some will argue that food is not addictive, one of the arguments being that you can’t get addicted to something essential for life. I ignore these scholarly arguments as a waste of time. My reaction is that individuals who argue against food as an addiction have not worked with the population of people with obesity like I have for all these years, and although everyone understands the negative consequences of overeating, it doesn’t mean they can stop. And by the way, not everyone who has food addiction has obesity, they may just have an eating addiction.

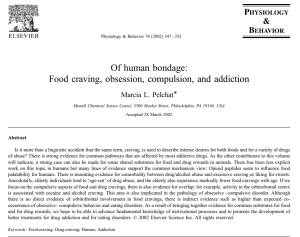

Some years later, scientists and psychologists started studying food and addiction, and the idea caught on. Dr. Marcia Pelchat, in 2002, in the journal Physiology and Behavior, published this paper with the colorful title, identifying the link between food and addiction.

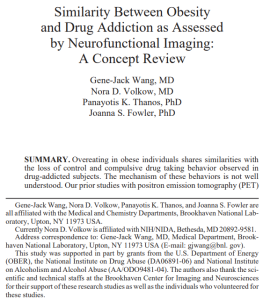

And then there are two of the most prolific researchers on food and addiction, Drs. Nora Volkow and Gene-Jack Wang. Dr Volkow is the Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health, and Dr. Wang is senior clinician and the clinical director of the Laboratory of Neuroimaging at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Volkow has published almost a thousand peer-reviewed articles, written 113 book chapters, manuscripts and articles, and edited four books on neuroscience and brain imaging for mental and substance use disorders.

Dr. Wang is no slouch either! His research focuses on PET Scan and MRI imaging of the neuro-psychiatric mechanisms and manifestations of alcoholism, drug addiction, ADHD, obesity and eating disorder in humans. He was the first to report the similarity of human brain circuits disruption in drug addiction and in obesity. He has published 281 original articles, 45 review articles, and 18 book chapters. If you do a search for either of them in Google, Google Scholar, or PubMed, you will get a sense of the breadth of their research, a significant amount in the area of food as a substance of abuse.

Then search for “food addiction” in the same search engines and you will find endless articles on food addiction by many scientists and psychologists. I expound on the credentials and accomplishments of Drs. Volkow and Wang to emphasize that they are two serious scientists studying the very serious issue of food addiction.

Drs. Volkow and Wang published this article in 2004:

Then in 2009, the psychologist Ashley Gearhardt Ph.D., developed the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS), published many articles on the subject, and argued for the idea that food addiction does exist. The YFAS is designed to show if individuals have behavior patterns similar to persons who are addicted to other substances of abuse, such as cocaine. In a 2021 meta-analysis (a review of many studies), Praxedes et al, published in the journal European Eating Disorders Review, used the YFAS and found that 20 percent of adults are addicted to food. In our program, we used the YFAS and found that 41% of our participants showed many patterns of behavior similar to persons with addiction to other substances of abuse. Below are two of the many articles published by Dr. Gearhardt.

Then there is this article in Bloomberg, also published in 2011:Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-11-02/fatty-foods-addictive-as-cocaine-in-growing-body-of-science

NEUROBIOLOGY: BRAIN IMAGING AND FOOD ADDICTION

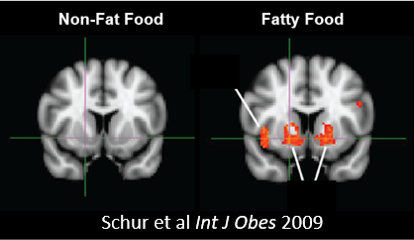

The image below captures the brain lighting up in regions of the brain interested in food. The next time you feel like your brain is lighting up because you’re thinking about food, you’re not imagining it. It is indeed lighting up in regions of the brain that create food cravings and likely stimulate what’s called the “reward pathway” in the brain, responsible for how rewarding and motivational food is for you. The reward and motivation pathway in the brain consists of the regions of the brain known as the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens. Interestingly, daily snacking on highly processed foods, or foods high in fat and sugar, rewire the brain’s reward circuits, increasing food cravings and making some foods more palatable than they already are, and I’m not talking broccoli. Most rats will choose sugar instead of cocaine, and similar observations have been made in humans, where highly processed and high fat/high sugar foods are overeaten to the point of vomiting, diarrhea, and what we call in our program, a “food hangover”.

I want to tell you that the lighting up of your brain while you look at food, think about food, or taste or smell certain foods, is NOT in your imagination. It is the neurobiology of your brain at work, and it overworks in some people more than in others. Overweight and having obesity is not your fault. It’s not a lack of self-discipline or willpower, nor a character flaw. The brain circuits of some individuals for food, appetite, and a decrease in appetite regulation, is in overdrive. Neurotransmitters that send aberrant appetite signals through the brain, hormonal imbalances, and dysregulation of appetite regulation are just some of the problems. Again, THIS IS NOT YOUR FAULT. You did not choose for this to happen, nor do you intentionally make it happen.

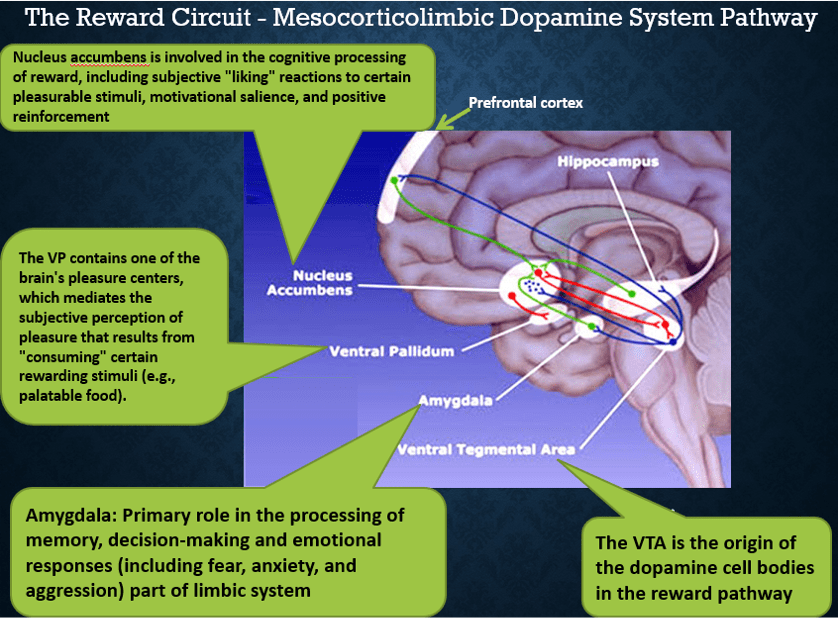

This next image is more complicated scientifically, but I will simplify as best I can. Dopamine is the “pleasure neurotransmitter” in the brain, produced by the region known as the ventral tegmental area (VTA), sending dopamine through reward circuits to the nucleus accumbens (one of the brain structures involved in drug dependency and food). The VTA secretes dopamine at high rates when you think, taste, smell, talk about, or see food in front of you or in your mind’s eye. Dopamine travels from the VTA to dopamine receptors in the brain that are responsible for giving you pleasure, sometimes known as the hedonic (pleasure) region of the brain. Vision of food is the strongest cue for food cravings, more than the other senses. “Out of sight, out of mind”, applies here as a way to control or prevent food cravings.

When you look at this image, think about the reward pathway. Human beings respond well to reinforcement, and reward is a reinforcement. In this case, the reward is the value of the food, what is known as “reward sensitivity”. When you satisfy a food craving by eating, you are rewarded, and the reward is reinforced each time you do it. If the food craving is caused by stress, for instance, and you eat to calm down, what you know as “emotional eating”, then that becomes your “go to” response to stress or anxiety. And over time, with more and more reward and reinforcement, the behavior becomes, as we like to say, more hard-wired, more automatic. And as the pathway, and the reinforcement, gets stronger and stronger, it begins to resemble addiction because it is as if the wiring has taken over the brain.

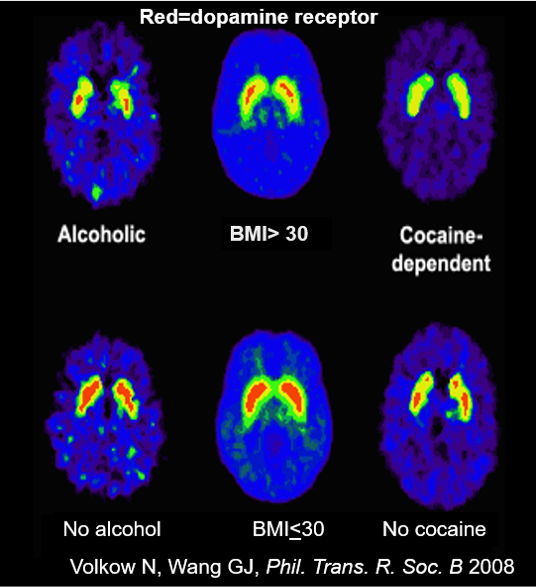

Based on the above description of reward and reinforcement, some scientists do not believe in addiction to food, they prefer to call it reinforcement. That’s a reasonable argument until you understand the role of dopamine receptors and what happens to them over time as you surrender to cravings and the wiring seems to take over. WHAT YOU SEE IN THE UPPER PANEL OF THE IMAGES BELOW are brain scans of persons addicted to alcohol, food (BMI greater > 30), and cocaine, compared in the lower panel to persons without these dependencies. The receptors are stained red by a special dye that shows up on the scan.

In these images, you see that fewer dopamine receptors are visible in the upper panel of the brains of individuals with substance abuse, or addiction, compared with more dopamine receptors visible in the lower panel because they do not have addictions. This is called “down-regulation” of the receptors, that is, they become less functional. As a result, individuals with addiction must consume more of the substance to “get their fix”. It’s as if the whole pathway is hijacked, which, if you ask individuals who experience this, may describe it just that way. Sometimes I describe it as “alien hand syndrome”. That is, you no longer have control over your own behavior as the brain is so reinforced by the behavior, so much so that dopamine receptors no longer function like they should. That’s how powerful the reward pathway can become.

This scenario above describes addiction as simply, perfectly, and clearly as possible. That is, you need your fix by consuming more substance because your dopamine and dopamine receptors don’t work as well as in non-addicted individuals. Again, THIS IS NOT YOUR FAULT. It is not a lack of will power, self-discipline, or a character flaw. Genetics, epigenetics, hormonal imbalances, neurotransmitter receptor down-regulation, excess food supply, highly processed foods, learned behaviors, and much more biology and psychology, causes this.

To read more, check out my blog on dopamine receptors by clicking HERE.

In Transformation Weight Control, and all the programs prior to this one that I have been involved with, I teach this to empower you and understand that it’s not your fault, and then we go to work teaching behavior, psychological, and physical strategies to help overcome it. We’re good at it at TWC, and it works. I’m not suggesting it’s easy, but individuals gain control over addictions all the time.

I would be remiss at this juncture not to mention the fact that the new GLP-1 receptor agonists, the weight control medications that have taken the country by storm, work on the reward pathway in the brain so that you experience fewer cravings and obsessing about food. As our patients report it, there is less “food noise” in their head. The fact that a medication can manage the disease of having obesity, and positively affect, or repair, pathways in the brain that are associated with addiction, is just more evidence that we are dealing with true addiction. And I repeat, IT IS NOT YOUR FAULT. What a relief it is to finally have help from medications that are finally effective.

PSYCHOLOGICAL (AND SOME PHYSICAL) FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH ADDICTION, SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND HAVING OBESITY

No article or blog about food addiction and having obesity would be complete without describing the association between childhood trauma and addiction or substance abuse as an adult, as well as the association between childhood trauma and having obesity as an adult.

In a groundbreaking study by Felitti and colleagues, published in 1998 in the journal, American Journal Of Preventive Medicine, the subject of what is known as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) is well described and defined as “traumatic events and unsafe environments occurring in children before the age of 18”. The ACEs include the incidence of emotional, physical, sexual maltreatment, neglect, substance abuse within the household, mental illness in the household, violence, and incarceration of a household member. In this paper, the authors describe the association between ACEs and death rates.

Later studies, such as that by Anda and colleagues in a 2006 issue of European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, describe some of the same ACEs and some additional: emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, substance abuse, mental illness, mother treated violently, parental separation or divorce, incarcerated household member, and serious household dysfunction.

In a slightly earlier study published in 2003 by Dube and colleagues in the journal Pediatrics, the authors show that compared with people with zero ACEs, people with ≥5 ACEs were 7- to 10-fold more likely to report illicit drug use problems and addiction to illicit drugs. So they clearly show a strong and significant association between ACEs and drug addiction.

And then there is the association between ACEs and having obesity. Hemmingson and colleagues published in a 2014 issue of obesity reviews, that four types of abuse — physical, emotional, sexual, or general abuse — and severe abuse as well, were all associated with having obesity as an adult. Their ACE results show:

1. a 29% greater risk of having adult obesity when there was physical abuse;

2. a 36% greater risk of having adult obesity when there was emotional abuse;

3. a 31% greater risk of having adult obesity when there was sexual abuse;

4. a 45% greater risk of having adult obesity when there was general abuse of many types; and

5. a 50% greater risk of having adult obesity when there was severe abuse.

The conclusion here is that Adverse Childhood Experiences are significantly associated with addiction, substance abuse, having obesity, and other psychological and physical disturbances. The data is indisputable.

At Transformation Weight Control, we take the view that having obesity as a child is associated with post traumatic stress as an adult. Perhaps not for everyone, as there is no such thing as all-or-nothing, but that the scars caused by childhood obesity track strongly into adulthood and cause emotional, psychological, physical, and many other types of mental and physical pathology and disturbances.

For instance, childhood obesity is associated with bullying, social teasing, victimization, low self-esteem, stigma, poor academic performance, anxiety, depression, societal bias, isolation, shame, guilt, self-blame and lack of self-compassion, social bonds and friendships (a study by Sabin in 2012 in PLoS One showed that two-thirds of 9- to 11-yarolds reported they would have more friends if they lost weight), body image disturbance (body dysmorphia) and excessive concern about weight, size, or shape, eating in secret, obsessive calorie counting, chronic dieting, and more.

A study by Puhl and colleagues in 2013 published in the journal Pediatrics, found that 71% of teens with obesity reported being bullied about their weight in the past year, and 33% reported bullying had persisted for more than 5 years. A study by Schwimmer in JAMA in 2003 revealed that children and adolescents with severe obesity had quality-of-life scores that were worse than age-matched children who had cancer.

The evidence supports the idea that adverse childhood experiences and trauma, including having childhood obesity, is associated with many negative physical and mental health problems, addiction, substance abuse, having obesity as an adult, and more.

NONE OF THIS IS YOUR FAULT

Finally, I want to reiterate that I focus on, and teach addiction to food, not to shame you and define you as an addict (which colleagues of mine have told me is exactly what would happen), but rather to empower you and help you understand that your weight, and any addiction to food you might experience, IS NOT YOUR FAULT. I can say that over and over again, the response to me teaching addiction has always been met with positive feedback and feelings of empowerment. And you should also always remember that people manage addictions all the time.

I recommend the following books:

-

-

“Relapse Prevention Counseling Workbook: Practical Exercises for Managing High-Risk Situations” by Terence T. Gorski;

-

“Relapse Prevention, Second Edition: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors 2nd Edition” by Alan Marlatt, and Judith Gordon.

-

“From the First Bite: A Complete Guide to Recovery from Food Addiction” by Kay Sheppard.

-

There’s also a little book I recommend called “Food for Thought: Daily Meditations for Overeaters (Hazelden Meditations)”, a lovely little book that has a brief paragraph or two for every day of the year to help you stay focused and get through the day. It’s described as “Daily readings for compulsive overeaters who seek to understand the role of food in their lives, supporting a life of physical, emotional, and spiritual balance.”

-

I also recommend this article published in Scientific American: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/food-can-be-literally-addictive-new-evidence-suggests/

-

© Richard Weil, M.Ed., CDE, 2024 All Rights Reserved